What do you call a scientist who isn’t a scientist?

***

Ask any Regular Jane off the street what they picture when they picture a scientist and they’ll likely say one of two things: a white lab coat or Albert Einstein. It’s a very common perspective, but it’s also increasingly inaccurate.

For years now, there has been a slowly-ramping crisis in the scientific community: there aren’t enough academic jobs to employ everyone who wants one. This is a serious problem for us as a scientific community, because so much of our process of training and equipping the next generation of scientists is focused on preparing people to become professors.*

The postdoc market has become the epicenter of this crisis. Postdocs are generally people who have committed to the academic route, having bypassed offramps of changing career paths at the end of the undergrad and grad school periods. We in the scientific community sometimes don’t really appreciate how weird the postdoc step sounds to people outside of it. After all, these are people who have just finished 5-7 years earning a Ph.D., who are then going back into the lab to do even more research before finally being able to be a professor somewhere. In a normal labor market, this isn’t a problem. But with reduced funding available for academic research, there are fewer and fewer professorships available for a widening pool of candidates.

Interestingly, this is a known theoretical problem in economics circles. It’s called a glamor labor market. Megan McArdle described this situation well in a recent article:

“[Glamor labor markets are markets where] a large number of aspiring entrants, who are poorly paid, but have a shot at fame and fortune if they reach the top slot. A small number of people in the top slots. And very little in between, in part thanks to the huge oversupply of labor at the bottom, which makes it cheaper to use three less experienced people than one person at a middling wage scale.” (link)

Sound familiar?

Our whole system for training scientists is geared toward training academics. Ask any science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) graduate student what they intended to do with their Ph.D., and I’ll bet you the majority will say either academics or industry, and most might look at you with a confused expression if you ask for options beyond those two.

Just as the academic market has contracted, so too has the industry market. Industrial pharmaceutical chemist positions have been disappearing as companies globalize their production systems. The slow recovery of our economy has hampered expansion of bench chemistry employment as well. Chemists graduating in today’s economy face one of the hardest job markets we’ve seen in a while.

I certainly never heard anyone talk about the difficulty of finding a job post-grad school when I arrived there. And if I’m being honest, I’m not sure I would have listened if they had. At 22, I was biased toward my own self-assurance of future domination, and frankly, had already picked my career path. Risk analysis was not in my portfolio of thinking at that point in my life. Luckily, going to grad school at the University of Michigan offered me an array of alternative choices, once I woke up to the reality that I didn’t want to be a professor anymore. I found my way into the science policy world, which married a lot of my interests together in a way that makes me feel like I’m still helping the world.

But sometimes, it’s hard to still feel like a scientist. I’m not at a bench, but I’m involved in work that has real and dramatic implications for scientific research and development in this country. I still use scientific knowledge and decision-making skills on a daily basis. I just haven’t worn the white lab coat in a while.

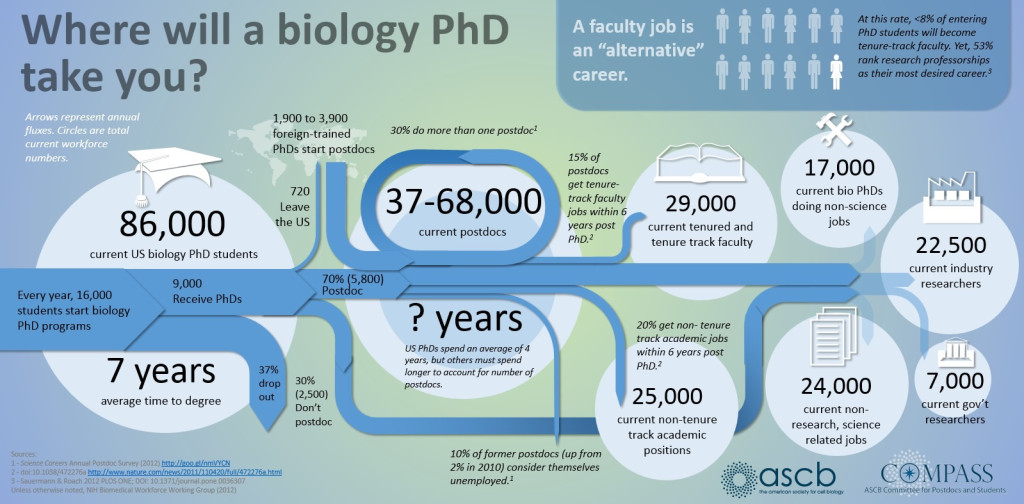

Recently, I stumbled onto this infographic from the American Society for Cell Biology:

Granted, this data is for the biology field, but I spent some time tracking down numbers on this for the chemistry community. By and large, the trend holds for chemistry as well. It has become so difficult to land an academic position, that the image of scientists as professors is no longer in the mainstream. At current rates, depending on the field, ~10% or less of the grad students entering each will become professors in the end.

This is why I hate the term “alternative science careers.” If only 10% of us are going to become academics, then the reality is that a faculty job IS an ‘alternative’ career.

The reality is that scientific and technical knowledge is becoming more critical to solving a whole host of societal problems. Without scientific experts who are willing to branch out and try new things, we have no way of leveraging that knowledge in places traditionally devoid of scientific talent. In part, this means it is incumbent on us to expand the definition of what it means to be an expert in something. We have a huge oversupply of scientists who are in it because they think science is interesting and wanted to investigate, learn, and probably change the world a bit. And we have a huge range of serious issues facing our society that need scientific experts to address them well.

Speaking from some personal experience, it’d be nice if we didn’t teach our young scientific minds that if they are leaving the lab, they aren’t real scientists. I think we forget sometimes that being a scientist is more than a profession: it’s an identity. Giving up that sense of self-identity to go do something new is a very difficult thing to do.

I’ve been out of graduate school for several years now, and have gotten to do some really cool things in the science policy space. I helped The National Academies write several studies, worked for Congress, helped write laws, advocated for causes I believe in, and worked in the President’s Administration. When I talk to scientists, they universally expresses some level of happiness that I’m here, trying to help incorporate science into governmental decision-making.

And I’ve come to accept that, in spite of all I’ve gotten to do, I will never again have the chance to be a professor. When I sit in meetings or attend conferences with scientists, I sometimes have to remind them that I know the language they speak. Our community doesn’t quite know how to incorporate an atypical scientist like myself into the fold without making them feel like impostors.

If there’s any positive outcome to the crisis in academic employment facing our community, it’s that more people seem to be taking that risk of trying something new. Our scientific diaspora is changing, and we need to start thinking about what that means for how we perceive ourselves as a community, and how we treat those who blaze the trail of new, expanded, unexpectedly different scientific careers.

***

What do you call a scientist who isn’t just a scientist?

I’d call them trailblazers.

*More reading on the academic job market:

- Too Many Science Students? (Megan McArdle, The Daily Beast)

- Too Many Postdocs, Not Enough Research Jobs (Jon Marcus, Higher Times Education)

- Does Science Produce Too Many PhD Graduates? (Neuroskeptic, Discover Blog)

- US Urged to Rethink Chemistry Graduate Education (Rebecca Trager, Chemistry World)

- Too Many Scientists? (Chemistry World)

- Are There Too Many Ph.D.s and Not Enough Jobs? (All Things Considered, NPR)

- The Postdoc Series: The Podcast (Julie Gould, NatureJobs)

- The Ph.D. Bust: America’s Awful Market for Young Scientists – In 7 Charts (Jordan Weissman, The Atlantic)

- Glut of Postdoc Researchers Stirs Quiet Crisis in Science (Carolyn Y. Johnson, The Boston Glob)

Photo credit: uncoolbob / CC BY-NC 2.0