By Lisa Greenhouse, NIST Historian

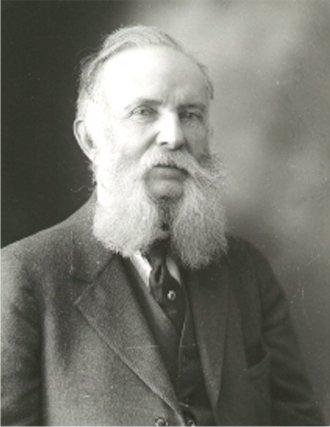

The annual Hillebrand Prize of the Chemical Society of Washington (CSW), awarded for original contributions to the science of chemistry by member(s) of CSW, is named for William F. Hillebrand (1853-1925), one of Washington’s most distinguished chemists. Hillebrand achieved such stature during his career in Washington, first with the Geological Survey and then with the Bureau of Standards, that his colleagues referred to him as the “Supreme Court of Chemistry.”

Hillebrand was indeed a judge and a critic but a reluctant one. As Chairman for many years of the Supervisory Committee on Standard Methods of Analysis of the American Chemical Society (ACS), he played a paramount role in judging which analytical methods would be published as ACS standards. As associate editor of the Journal of the American Chemical Society and assistant editor of Chemical Abstracts and the Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, the latter of which he founded, Hillebrand placed himself in the delicate position of having to critique and often reject the work of his professional peers. He performed these duties with great integrity but also with some unhappiness, never feeling good about disappointing his colleagues.

In several addresses to scientific societies, Hillebrand was sharply critical of what was then the growing tendency of his profession to make incomplete chemical analyses of samples, leaving out elements present in small amounts and leaving out determinations of rare elements that were thought not to be useful. This was so even when important uses for rare elements continued to be discovered. Hillebrand, an analytical geochemist by training, deplored this trend toward incompleteness and was outspoken in his criticism.

Hillebrand’s conviction that analytical chemistry should be exacting was indicative of his perfectionism. More than a judge of others, he was a judge of himself. He always regretted that he had what he considered an inadequate grasp of mathematics and English composition, and he didn’t fail to mention these deficiencies in autobiographical notes. He modestly referred to Thomas H. Norton, his classmate at the University of Heidelberg, where Hillebrand received his PhD, summa cum laude, in 1875, as having “superior mental power” to his own. He struggled with embarrassment over his failure to find terrestrial helium in a sample of uraninite, which he had analyzed in 1887, an error pointed up by Sir William Ramsay’s later discovery of helium in a variety of uraninite.

After Heidelberg, Hillebrand studied at the Mining Academy at Freiberg, Germany. Thus prepared, Hillebrand returned to America to pursue a career as a geochemist. In 1880, after running a private assaying firm in Leadville, Colorado, a silver mining boomtown, he took a job as an analytical chemist with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Denver laboratory. He was soon transferred to Washington where he made major contributions to the understanding of silicate rocks.

In 1908, Hillebrand moved to the Bureau of Standards (founded in 1901 as a national standards laboratory) as Chief Chemist. Hillebrand, with scant resources and a few staff members, set out on a groundbreaking path of preparing and providing well-characterized samples necessary for American industry to check its analytical methods, techniques, and instruments. The Standard Reference Materials Program that Hillebrand established continues to be one of the most significant missions of the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

To nominate someone for the Hillebrand Prize, click here!

To read about past winners of the Hillebrand Prize, click here.